(Image: iStock)

I’m a reporter. I’ve never worked for a market research company.

My understanding of market research, quantitative or qualitative, is thus minimum, to say the least.

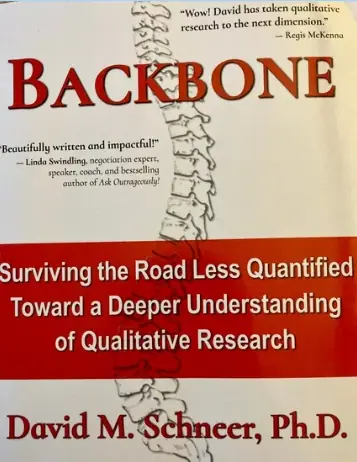

David Schneer’s latest book “Backbone”, however, made me see commonalities between the work of qualitative market researchers and what reporters strive to do.

I suddenly felt closer to qualitative researchers and realized that I might have something to say about it. Hence, this post.

Schneer’s book’s subhead — “Surviving the Road Less Quantified Toward a Deeper Understanding of Qualitative Research” — explains key building blocks, or individual “traits” that the author believes could help one become a better qualitative researcher.

Schneer cites “curiosity, preparedness, extroversion, synthesizing complexity, listening with your eyes, grit and being venturous.” He describes the significance of each trait in subsequent chapters.

In a style neither formulaic nor pedantic, Schneer gets to the ultimate question: “Why qualitative research?” His personal anecdotes involve his own father, his colleagues and even Intel Corp.’s legendary CEO, Andy Grove.

So, what got Schneer into the field of qualitative research?

It was theology. Specifically, Schneer studied the methods of Apologetic theologians who defend their faith through argumentation. This discipline, Schneer found, could have used qualtitative research.

Qualitative research is ‘a methodology designed for depth of understanding rather than statistical reliability or projectability.’

David Schneer

In “Backbone,” Schneer quotes Donald Carson, a prolific Apologist, who once wrote:

Even when the standard polls provide useful and interesting data, a depth dimension is often missing.

Schneer’s interpretation: “Without even knowing it, Carson is yearning for more than just the numbers.”

This insight leads Schneer to define qualitative research as sitting at “the intersection between depth of information and dialog.” In other words, it’s “a methodology designed for depth of understanding rather than statistical reliability or projectability.”

The art of ‘reading’ people

Schneer insists that qualitative research can ensure that “the right questions are being asked (that is, quantitative research can be statistically reliable, but that doesn’t mean it is always valid).” It can also ensure “important questions are not excluded (did a particular survey miss any important questions or topics?)”

In essence, qualitative research asks probing questions and hones the art of reading people.

In one chapter, “Listening with Your Eyes,” Schneer stresses the critical need to read “body language” in qualitative research.

While reporters are not trained behavioral analysts, they learn how to discern clues by watching and interpreting how interviewees respond to questions — a pregnant pause, an evasion, a long gaze up at the ceiling, an eye movement that betrays a likely lie.

But trained qualitative researchers push body language expertise to a higher level.

Schneer asks: “Have you noticed instances where someone’s words do not match their demeanor or their body language? Can you recall the details?”

Qualitative researchers in fact leverage the art of observation to spot contradictions. Schneer enumerates telltale signs displayed by a respondent during an interview:

Her arms were folded. She was leaning back. Her feet were pointing toward the door. One corner of her mouth quickly moved up ever so slightly. A wayward index finger began to tap to an unknown beat. She began to pick lint on her blazer, but there was no lint.

Schneer asks an interviewee about a product concept he is presenting. “Tell me, what do you think?” She responds, “Oh I like it. I’d buy it. Certainly.”

Schneer notes, “But that’s not what her body said…” After probing further, he said, he was able to determine her doubts about the concept.

Going beyond ‘narrative’

After reading “Backbone,” I called the author.

Although I’m not a market researcher, I take stock of what I am hearing from the companies I interview.

Lately, more than ever, corporations strive to create their own “narratives” and to stake their “claims,” often hiring former reporters to help spin the yarn. I find it increasingly difficult to ferret out the truth. Too many stories fed to the media, whether technology or business, seem to convey a story line predetermined before they were even written.

This phenomenon is particularly pronounced in political coverage.

I knew Schneer doesn’t specialize in election polling, but I was curious about so many poll results and focus-group analyses proved to be seriously inaccurate after all. The same problem has skewed media coverage of political trends.

It’s obvious that people often tell pollsters and reporters not what they really think, but what they think the interviewer wants to hear.

This, Schneer acknowledged, is called “confirmed bias.” This is where market research could go so wrong — confirming or justifying an unproven belief — that it sullies the reputation of both the researcher and the client who bought the research.

If “Backbone” is right, this is precisely where qualitative research comes in.

Schneer cited the example of a market study he did for a $10 billion MCU vendor who wanted to measure design engineers’ concerns about sustainability issues. The company wanted to know how best to inject “sustainability” stories into their website and marketing materials.

Unsurprisingly, focus group members spun Schneer politically-correct views that they thought the market researchers wanted to hear. But by combining human nonverbal intelligence interpretation with AI, Schneer said he was able to debunk what his client thought they heard in the focus group.

While I’m just beginning to learn the art of qualitative research, Schneer’s “Backbone” has provided me both a primer and an argument for the value of qualitative research.

Leading market researchers in the electronics industry

Although I’m hardly an expert on the ins and outs of the discipline, I’ve worked occasionally with market researcher. As a reporter, I sought, for example, to get “the pulse of the industry” on products, technologies, market trends and salary surveys.

Although I was only peripherally involved, the most memorable qualitative research we did at that time when I was working at the previous publication was “The Mind of the Engineer.” The architects of the project were Jim Warrick and Mark Skillings.

Incidentally, Schneer has worked Warrick, at one point, conducting market research projects with the same accounts.

Schneer is now CEO of Merrill Research. As part of a loosely connected pioneering group of qualitative researchers including Warrick and Skillings, Schneer takes pride in knowing technologies, with roots in the semiconductor segment. As suggested by Schneer’s book, the application of qualitative research will help industry leaders to ask the right questions about their own business plans and technologies and to better understand not just what people say to them, but how they say it.

Book:

BACKBONE: Surviving the Road Less Quantified – Toward a Deeper Understanding of Qualitative Research.

Author:

David M. Schneer

Publisher:

Quandrivium Libri (published in 2024)

Junko Yoshida is the editor in chief of The Ojo-Yoshida Report. She can be reached at [email protected].

Copyright permission/reprint service of a full TechSplicit story is available for promotional use on your website, marketing materials and social media promotions. Please send us an email at [email protected] for details.