Sam Altman, CEO of OpenAI, and Satya Nadella, CEO of Microsoft at Davos (Image: The Economist )

By Girish Mhatre

How to bamboozle with BS

The “Sam and Satya” show, heralding the dawn of an AI-infused digital utopia, took Davos by storm last week; by some accounts AI – specifically, generative AI, of which ChatGPT and its ilk are a subset – was the talk of the town at the annual World Economic Forum. Business is bracing for a revolution spawned by what is clearly a transformational technology and Sam Altman (CEO of OpenAI) and Satya Nadella (CEO, Microsoft) – dubbed “rock stars of technology” by the Economist magazine – clearly want to position their partnership at the vanguard.

As befits the CEO of the world’s largest company, Microsoft’s Nadella is focused on the impact of AI on the bottom line for his organization. Ever the salesman, he couches his pitch in terms of “expertise at your fingertips” for users of his AI -powered products and a “productivity driver [not seen} since the PC.” And that’s just for starters. AI will get better “in non-linear ways,” he promises, until it becomes “a general-purpose technology for all knowledge work.”

Altman, whose company, OpenAI, is the progenitor of ChatGPT(x), is more expansive; With a touch of evangelical fervor, he declares AI the cornerstone of “technological prosperity” for the world.

That technology is the most potent productivity driver and – eventually – a sure path to prosperity is an article of faith long preached by techno optimists. Call it the Silicon Valley ethic.

But a closer look reveals that the future they envision is flawed. It is, in fact, elitist and morally vacuous. The coming of an uplifting Rapture for some may prove to be a descent into Hell for society at large.

That technology is the most potent productivity driver and – eventually – a sure path to prosperity is an article of faith long preached by techno optimists. Call it the Silicon Valley ethic. “Technological prosperity is the most important ingredient to a much better future,” avers Altman.

History, however, does not support that optimistic scenario: Starting with the advent of the PC, and through successive generational upheavals (the Internet, mobile computing, cloud computing, to name a few), tech has not delivered on the promises of its paladins. Though it may have conferred vast riches on a select few, viewed through a macro lens, technology has failed to bestow the expected benefits of increased productivity on society at large. Nor has it spread prosperity widely through the American population.

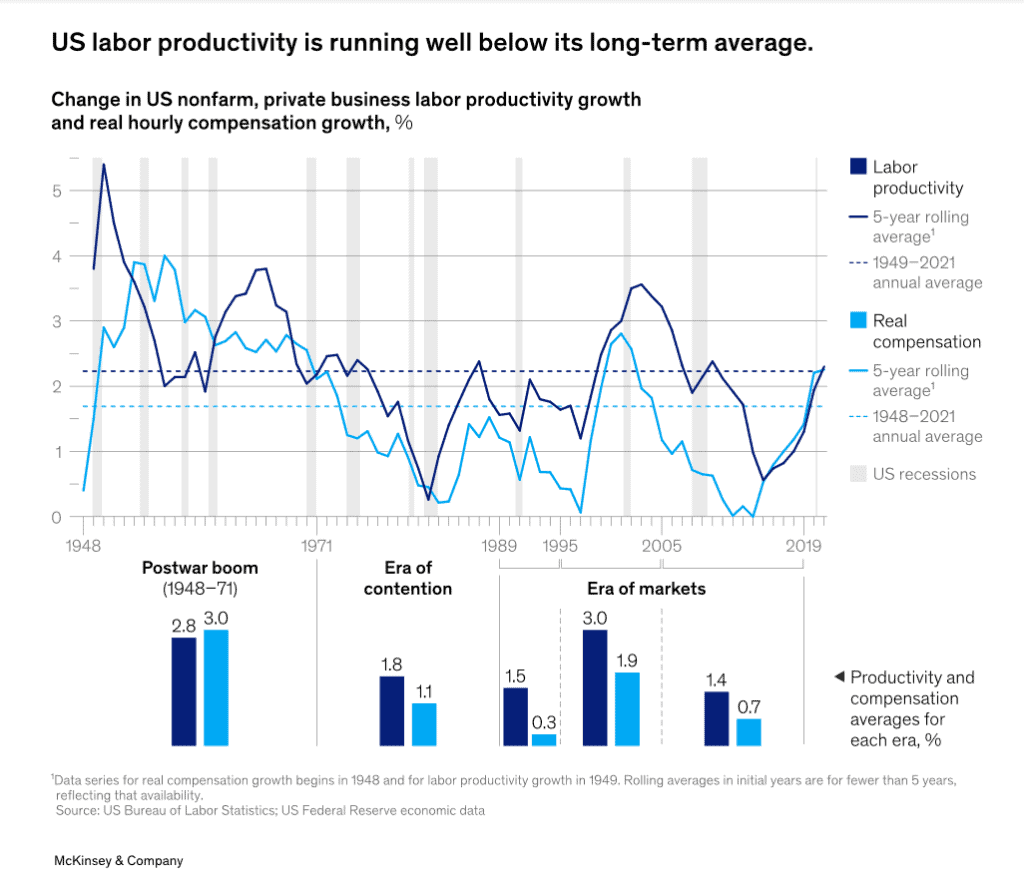

An analysis of labor productivity – defined as economic output per hour worked – by the McKinsey Global Institute, based on data sets compiled by the US Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) and the US Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA), is instructive:

“Labor productivity growth has been the engine of US economic power and prosperity since World War II, adding 2.2 percent annually to economic growth and contributing mightily to a 1.7 percent annual gain in real incomes.

“If the US economy were a car, the engine has been sputtering for a while. In the past 15 years, productivity growth has averaged just 1.4 percent, even as incredible advances in digital technology put a supercomputer in every pocket. “

“You can see the computer age everywhere but in the productivity statistics,” said Nobel prizewinning economist Robert Solow, way back in 1987. The quote holds through successive generations of technology.

Worse, “The link between productivity growth and real incomes has weakened. In the postwar boom from 1948–70, incomes grew at 3.0 percent annually, while productivity growth averaged 2.8 percent. More recently, real incomes have grown at 0.7 percent, well below the 1.4 percent gains in productivity.”

The standard (and tiresome) riposte to such an exposition on productivity is to denigrate the methodology.

In their recent book, “Power and Progress: Our Thousand-Year Struggle Over Technology and Prosperity,” MIT professors Daron Acemoglu and Simon Johnson report on some of the criticism leveled against productivity measurements: “Google’s chief economist, Hal Varian, argues that slow productivity growth is rooted in mismeasurement: we are not accurately incorporating consumer benefits from products such as smartphones that simultaneously act like cameras, computers, global positioning devices, and music players. Nor are we appreciating the true productivity gains from better search engines and abundant information on the web. The chief economist of Goldman Sachs, Jan Hatzius, agrees: ‘We think it is more likely that the statisticians are having a harder and harder time accurately measuring productivity growth, especially in the technology sector.’ He reckons that the true productivity growth of the US economy since 2000 could be several times greater than statistical agencies’ estimates.”

To counter that charge, Acemoglu and Johnson turn to a measurement called total factor productivity (TFP). TFP considers all inputs, including labor, capital, materials, and technology, and measures the overall efficiency of business in producing goods or services. Thus, products that significantly increase consumer welfare should translate into much higher TFP growth. But that is not the case.

“US average growth [in TFP] since 1980 has been less than 0.7 percent, compared to TFP growth of approximately 2.2 percent between the 1940s and 1970s. This is a remarkable difference: it means that if TFP growth had remained as high as it had been in the 1950s and 1960s, every year since 1980 the US economy would have had a 1.5 percent higher GDP growth rate. The productivity slowdown is not just a problem of the era following the global financial crisis of 2008. US productivity growth between the booming years of 2000 and 2007 was less than 1 percent. This evidence notwithstanding, technology leaders maintain that we are lucky to be alive in this age of technology and innovation.”

“Moreover, measurement problems cannot account for the current productivity slowdown; industries with greater investment in digital technologies show neither differential productivity gains nor any evidence of faster quality improvements than those that are less digital.”

It’s not just the hype machine of the tech titans and their Wall Street enablers that continues to propagate the productivity myth. Journalists everywhere have drunk the Kool-Aid, too. Case in point: The New York Times journalist Neil Irwin spins it thus, “We’re in the golden age of innovation, an era in which digital technology is transforming the underpinnings of human existence.”

In fact, income and wealth inequality in the United States is substantially higher than in almost any other developed nation, and it is on the rise.

The Council on Foreign Relations

If the past is prologue, the history of income and wealth inequality in the US belies Sam Altman’s assertion that “Technological prosperity is the most important ingredient to a much better future.” He’s right on one count, though: For the top one percent on the income scale prosperity has indeed tracked the increasing pervasiveness of technology. The wealthiest of the wealthy have left the rest of their fellow Americans in the dust: “Income inequality in the United States has been rising for decades, with the incomes of the highest echelon of earners rapidly outpacing the rest of the population. Even among high earners, income gains have been heavily skewed toward the top of that bracket, “according to the Council on Foreign Relations. “In fact, income and wealth inequality in the United States is substantially higher than in almost any other developed nation, and it is on the rise.” All this in the country that invented the PC, the internet, the smart phone and the computing cloud. Not only is there no evidence that technological progress has created widespread prosperity, rather there is scads of evidence that it has done the opposite – it has concentrated prosperity at the very high end of the income scale.

In fact, the problem is worsening. “The scale of US inequality relative to other countries is captured by the steady rise in the U.S. Gini coefficient, a measure of a country’s economic inequality that ranges from zero (completely equal) to one hundred (completely unequal). The United States’ Gini coefficient was forty in 2019—the same as Bulgaria’s and Turkey’s, and significantly higher than that of Canada, France, and Germany—according to the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), a group of advanced economies.”

Inequality in income translates to inequality of opportunity. When those at the low end of income distribution are deprived of their potential, demand inevitably weakens, decelerating the economy. And, over time the social fabric wears thin. “Excessive inequality can also erode social cohesion, lead to political polarization, and lower economic growth,” according to the International Monetary Fund.

So, why would these so-called rock stars keep touting, brazenly, the benefits of tech-driven productivity and prosperity in the face of incontrovertible historical evidence to the contrary? Surely, they are not ignorant of history. Perhaps the tyranny of the stock market creates blind spots?

Or is it something more insidious? Are they trying to distract us from the elephant in the room – AI as a misinformation diffusion machine without parallel? It’s an elephant that looms larger as the United States barrels toward the most consequential election of its history.

Already, AI generated “deep fakes” are roiling the body politic. AI “destabilizes the concept of truth itself,” says Libby Lange, an analyst at the misinformation tracking organization Graphika. “If everything could be fake, and if everyone’s claiming everything is fake or manipulated in some way, there’s really no sense of ground truth. Politically motivated actors, especially, can take whatever interpretation they choose.”

It’s unconscionable that the tech overlords would not even care to acknowledge the great threat to democracy, enabled by the products they put on the market. It’s Irresponsible – morally reprehensible, even – to babble on about productivity and prosperity when this country is facing an existential crisis. What good is the bottom line when truth itself is under attack?

Girish Mhatre is the former editor-in-chief and publisher of EE Times. The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and do not necessarily represent the views of the Ojo-Yoshida Report.

Copyright permission/reprint service of a full TechSplicit story is available for promotional use on your website, marketing materials and social media promotions. Please send us an email at [email protected] for details.