Semiconductor Technology News & Analysis | The Ojo-Yoshida Report

Technology: Featured Articles

Latest Technology News

Embedded Quest at Nuremberg

Who Wants Rapidus in Silicon Valley?

US Semiconductor Hegemony is Real and Unassailable

Smart vs. Useful

Acute Shiny Object Syndrome Can Ruin You

The Audacity of Tenstorrent

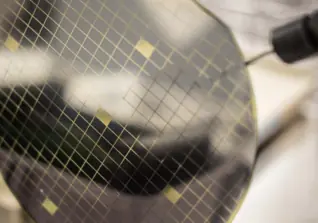

TSMC Fabs Operating Close to Capacity after Earthquake

Microchip: ‘Shared Pains’ in the Wake of a Supercycle

ST’s Key to Unlock China: ‘Manufacturing’

Intel Foundry Charts a Course to Breakeven

Jeff Bier: What Changed From VCRs to Software-Defined Vision?

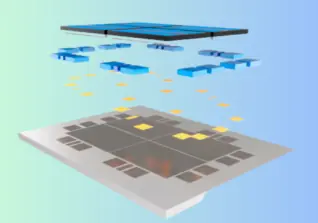

Players: Who’s Who in Chiplets

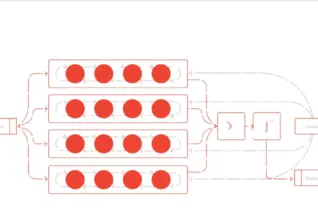

Growing Chiplet Ecosystem In a Snapshot

The Chiplet Revolution: Where We Stand Today

NXP Nudges OEMs Toward Software-First Design

Are Tsetlin Machines About to Reframe AI?

Where Nvidia’s Huang Went Wrong on Thomas Edison vs. AI

What Will Nvidia Do for an Encore?

Oculi’s ‘Software-Defined’ Vision Sensor Is Fresh and Foreign

The Unfulfilled Promise of Silicon Carbide

Partner Content

This Month

Testimonials

Timely and provocative

The Ojo-Yoshida Report is timely, insightful and sometimes provocative. I always learn something valuable in each edition, intelligent perspectives about our industry you cannot get anywhere else. Thank you and keep up the great work!

Renaissance in semiconductor insight

Junko and Bolaji are kickstarting a renaissance in semiconductor insight! It’s so rare these days to find such a wealth of timely, thoughtful coverage. But OYR manages to produce, every week. Well done!

Knowledgeable and insightful

When I heard that Junko and Bolaji were launching The Ojo Yoshida Report, I instantly got out my credit card and became their first paid subscriber. Junko and Bolaji are uniquely knowledgeable and insightful about our industry, and are constantly asking important questions. I never fail to learn from their reporting.

Uncompromising

I find The Ojo-Yoshida Report one of the most uncompromising and worth reading reports in the ADAS / AV industry.

Understand and influence the tech trajectory

The tech industry is vibrant, complex, and important. High-quality analysis & reporting is crucial to understand & influence the trajectory and impact of tech. Junko Yoshida and Bolaji Ojo are the voice. I highly recommend checking out the ojoyoshidareport.com.

What the news means

I don’t need news, I need intelligent insight. That’s why I read Ojo-Yoshida Report. It’s challenging interviews with industry experts, informative podcasts and knowledge-enhancing content. It’s Junko Yoshida and Bolaji Ojo at their finest. It’s the source I use to find out what the news means.

How do you get started in autonomous vehicles?

A lot of people ask me how to get started in autonomous vehicles. I started by reading what few great blogs/newsletters exist in the space. One of them is the Ojo-Yoshida Report, from Junko Yoshida & Bolaji Ojo. Paid sub, but quality is worth it.