Mobileye: Now, Next, Beyond - CES 2023 Press Conference with Prof. Amnon Shashua (Image: Mobileye)

By Colin Barnden

What’s at stake:

Mobileye has bet the house on eyes-off driving. But who is liable when the system is activated; is it safe for other road users; and how many automakers will even take the risk?

At CES in January, CEO Amnon Shashua presented his keynote “Mobileye: Now, Next, Beyond.” The YouTube video is here, and a summary of Mobileye’s CES announcements is here.

Shashua’s main claim was the introduction of eyes-off driving across a full range of operational design domains (ODDs), including highways and arterial, rural, and urban roads. He said: “You can go to sleep. You can do whatever you like.”

Absent was discussion of legal liability, international regulations permitting automated driving on public roads, and the safety of vulnerable road users (VRUs) around eyes-off technology.

Let’s get into the details of the keynote and take a closer look at some of Shashua’s claims.

Hands, eyes, and shoulders too

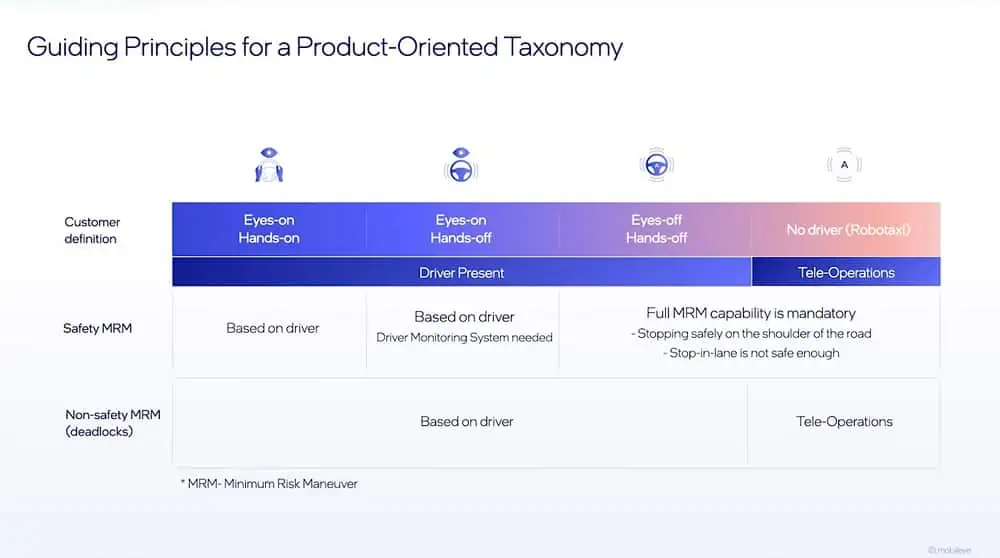

Beginning at 11:12 in the video, Shashua announces Mobileye’s divergence from the levels of driving automation described in SAE International’s Standard J3016.

The discourse today is Level 2, Level 3, Level 4. This taxonomy is good for engineers, it’s not good to talk about in a product-oriented language. We created our own language which says there is “eyes-on/eyes-off,” there is “hands-on/hands-off,” there is “a driver or no driver.”

He continues:

When you have an eyes-off system, there is no need to expect a driver to do anything. It means that, say you have a hands-off/eyes-off system designed for a highway ODD. You punch in an address, once you get onto a highway, you can let go – legally. That’s the whole idea of eyes-off. You can go to sleep. You can do whatever you like.

Shashua continues to explain that once the car exits the last highway of its route and reaches the edge of the ODD, it needs the driver to take back control, but doesn’t rely on that.

It needs to have the mechanism to stop safely on the side. This is called Minimum Risk Maneuver. But stop on the shoulder, not stop in-lane. Stopping in-lane is not safe, or not sufficiently safe.

He summarizes:

Once it’s activated, the driver doesn’t need to do anything because the car can, once it finishes the ODD, exit and stop on the shoulder.

Observe the ambiguity in meaning of the term “driver.” Shashua uses it in the context of the human sitting behind the wheel, while simultaneously describing the Mobileye driver as performing the driving task. The issue of liability is not discussed, having stated the human can go to sleep.

From eyes-on to eyes-off

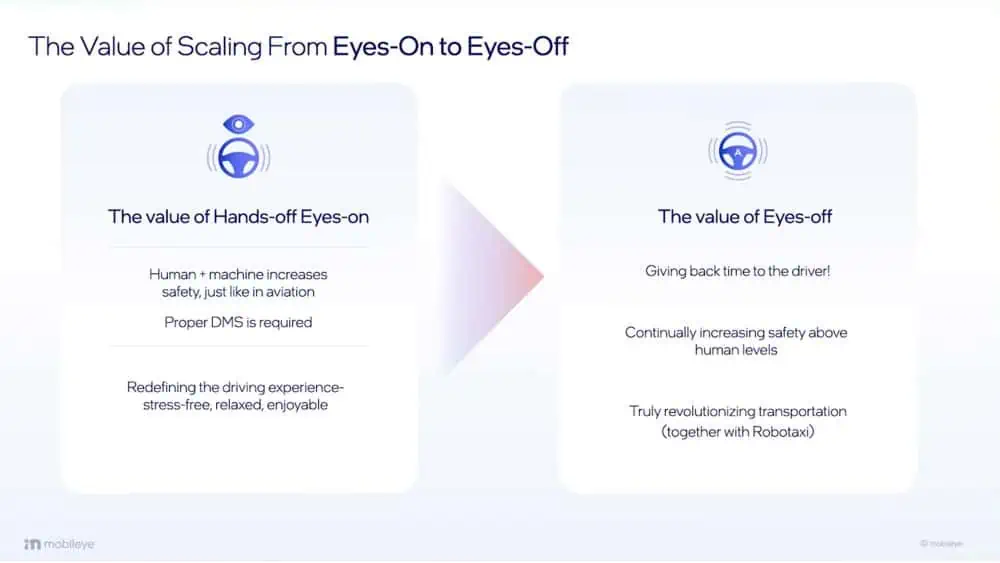

Starting at 14:10, Shashua explains the operation of a hands-off/eyes-on system:

When talking about the hands-off/eyes-on system, this is an interaction between man and machine. If you have a good driver monitoring system, with the camera watching the driver, then you can create a very good interaction between man and machine, in which the man or woman is supervising the machine. This interaction creates a high level of safety.

He then pivots to an eyes-off system:

Today we’re very busy, the roads are very congested. I want to navigate from Point A to Point B. 90 percent of the time is within the ODD of the eyes-off [system]. I activate it and read a book. It buys back time. A very different value proposition.

Shashua proceeds to make the boldest claims of the keynote:

Of course, it increases safety because the system is at a higher safety than a human. So, it also increases safety, but really the value proposition, why do you want to pay money for it beyond increasing safety, is the fact you buy your time back.

He attempts to explain these statements later in the keynote.

Mobileye everywhere

Starting at 16:30, Shashua describes Mobileye’s roadmap of ODDs leading to operation everywhere.

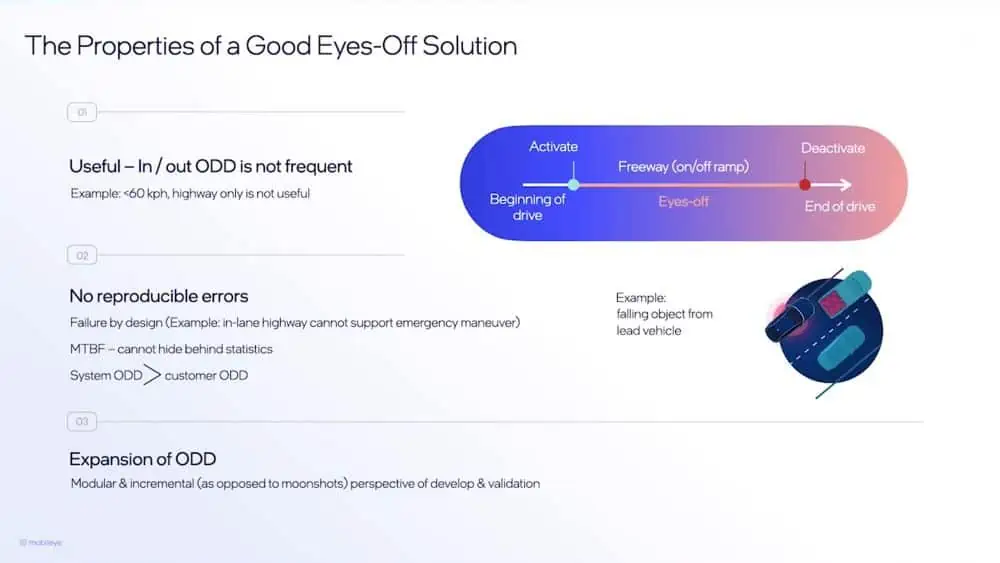

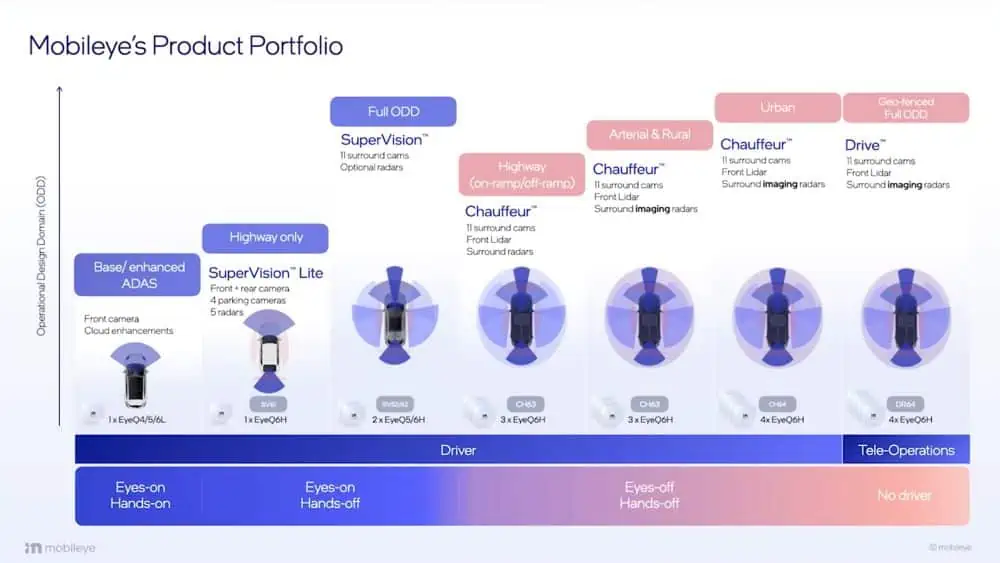

When we talk about eyes-off, there are ODDs. Highway only, below 60 kilometers per hour (kph), in lane. So, the car does not change lane. Many carmakers are introducing this kind of ODD in the next few years. Second ODD is the same thing, but up to 130kph.

The next ODD is the car can go on-ramp, off-ramp autonomously. You punch in an address, and to navigate to that address you need to go through five different highways. The system would do this autonomously. Next ODD you add arterial roads with traffic lights and then with signal traffic, signal junctions. The next one is rural.

Shashua references various types of ODD and refers specifically to autonomous operation. However, no description of the legal liability for operating this system is given, neither does he provide a definition of “autonomous.”

Clearly, an autonomous system must be liable for its driving decisions, else it isn’t autonomous.

Absent is discussion of international regulations permitting automated driving on various categories of public road. Let’s briefly review the most important one.

UN Regulation 157 for Automated Lane Keeping Systems (ALKS) came into effect in January 2021, and permits operation up to a maximum of 60kph. In June 2022 the regulation was extended to allow automated driving up to 130kph.

Regulation 157 states:

ALKS can be activated under certain conditions on roads where pedestrians and cyclists are prohibited and which, by design, are equipped with a physical separation that divides the traffic moving in opposite directions and prevent traffic from cutting across the path of the vehicle.

At 17:30 Shashua says:

The useful tipping point is when it’s highways, on- and off-ramp, up to 130kph. Anything below that is not that useful. So, the useful tipping point is starting from ODD 3 in this chart.

Thus, despite Shashua’s claims, the international legal position for ODDs 4, 5, and 6 is currently unclear, and no further details were provided in the presentation.

Shashua also implied comparisons with Tesla’s FSD (formerly known as Full Self-Driving) and GM’s Ultra Cruise, both of which are systems where the human supervisor is liable for decisions made by the machine driver, and where the human is required to maintain eyes on the road at all times.

The presentation then pivots from ODDs to discussion of the properties of a good eyes-off solution. Shashua says:

The first, it has to be useful. If it’s not useful, then why go through this trouble? The second we call “no reproducible errors.” It means you cannot hide behind statistics. The third one is expansion of ODD.

Let’s sidestep Shashua’s spin and list three alternative properties of a good eyes-off system:

1, Validated and verified as safe to operate.

2. The human sitting behind the steering wheel can neither misunderstand nor misinterpret their legal liability for operating the system on public roads in proximity to VRUs.

3. The human understands at all times when they are driving the vehicle and when they are supervising the machine driving the vehicle. This ambiguity in responsibility is called “Mode Confusion.”

Autonowashing?

At 24:58, Shashua introduces Mobileye’s portfolio:

On the left hand is the base and enhanced driving assist, this is front-facing camera. The third column is SuperVision. It has the resolution to do hands-off driving in a full ODD, but it doesn’t have the mean time between failure to allow eyes-off. The second column is what we call SuperVision Lite, only for highways.

As explained, UN Regulation 157 permits operation only on divided highways, and then only where VRUs such as pedestrians and cyclists are prohibited. Thus, the international legal position for “Full ODD SuperVision” is unclear and unexplained.

Shashua continues:

In the fourth column and above is the eyes-off system. We call this the Chauffeur family. First highway on-/off-ramp. Then comes arterial and rural, then urban. Once we reach full ODD, it’s robotaxi, but we need to add tele-operation, which we do not need in consumer AV.

He reasserts eyes-off operation and reaffirms the roadmap to full ODD for operation everywhere. The invitation is to see Chauffeur as an autonomous system which drives everywhere, reinforced by Shashua’s earlier comment: “You can go to sleep. You can do whatever you like.”

Mobileye calls this Chauffeur. Others might call this Autonowashing.

Hiding behind statistics

Starting at 36:52, Shashua begins to discuss proving system validation:

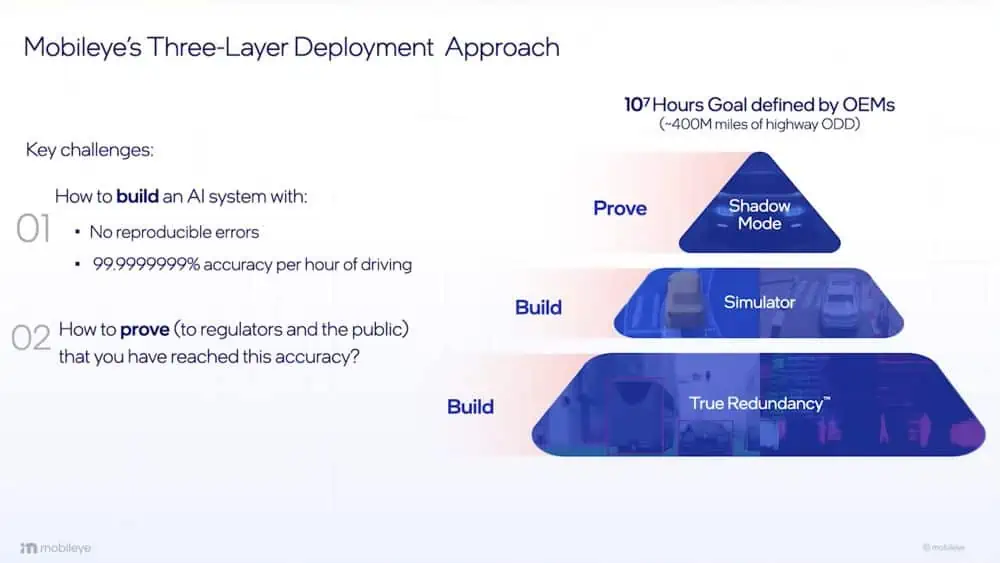

Talking about highway ODD, the requirement is 107 hours of mean time between failure. That means you need to prove the car will drive ten million miles without creating an accident.

Observe that he specifically refers to “mean time between failure,” and “without creating an accident,” as opposed to “not involved in a crash.”

He continues:

I need to prove to regulators, I need to prove to the public, that the system really meets that accuracy goal. So, we have three layers. The first two layers are “build,” the last layer is “prove.”

Again, observe that he carefully refers to “proof,” and to an “accuracy goal,” as opposed to any specific references to safety, or how safe is safe enough.

Shashua proceeds to dish up a nothingburger with a side order of word salad:

The way we build a system is through complete redundancy. SuperVision is only cameras. As you saw, SuperVision can do full end-to-end autonomous driving, but it requires eyes on because it’s not sufficiently safe to say that I’m better than a human driver. So we have a subsystem of only cameras. A subsystem of only active sensors – each of them building an environmental model, a sensing state, completely separate from the other. Because we’re talking about different modalities. It looks like it’s statistically independent, I cannot prove it’s statistically independent and probably, maybe it’s 99.9% statistically independent, but not 100%. But if it were statistically independent, I can then take the product. So say I collect 10,000 hours of driving of real data to validate the camera-only subsystem. And then I collect 1,000 hours of real data to validate the radar/lidar system. If those were statistically independent, then the meantime between failure is the product. If they were completely independent – 10 to the seven (107). This claim will not stand in court, because I cannot prove this. Just like in aviation, you have redundancies. Nobody proves, nobody comes and claims that those redundant systems are statistically independent. You just create more and more redundant systems. So this is not a proving methodology, this is a building methodology. From a robustness point of view, it makes a lot of sense. So this is how we build the system.

Again, Shashua makes no specific references to safety. He goes on to discuss the role of simulation starting at 40:47, and of “shadow mode” starting at 43:54.

And that’s the keynote. Lots of headline grabbing hoopla and hype for eyes-off systems, but no discussion of liability, trust, or safe operation. Having read the analysis of the presentation, ask yourself the following questions:

- Would you bet your life on Mobileye’s “Chauffeur” eyes-off driver?

- Would you bet someone else’s life on it?

- Would you risk possible jail time by engaging it on a public road and it killed someone?

- Are you certain it is safer than a human driver?

Mobileye was asked for comment on the issue of liability. It said:

Like all automotive suppliers, Mobileye works closely with customers to address liability concerns, taking into consideration different levels of autonomy, changing scope of ODD, drivers’ engagement and OEMs role. We anticipate that highly automated systems will require new approaches to liability, and our entire system architecture has been designed to develop and deploy driver assist and automation in a responsible, scalable, and transparent manner.

Still confused? BMW’s CEO Oliver Zipse is clear on the matter: “We don’t take the risk.” Other automakers are unlikely to take on the liability risk either.

In reality we all know who is liable for an eyes-off system: That will be the poor sucker sitting behind the wheel, who believed the CES hype but didn’t read the fine print in the terms and conditions.

Bottom line:

If Mobileye won’t take liability for operation of its eyes-off system, why should anybody else?

Colin Barnden is principal analyst at Semicast Research. He can be reached at colin.barnden@semicast.net.

Copyright permission/reprint service of a full Ojo-Yoshida Report story is available for promotional use on your website, marketing materials and social media promotions. Please send us an email at talktous@ojoyoshidareport.com for details.