(Image: Volkswagen)

By David Benjamin

Unwittingly, when I was about ten, I was becoming a movie maven. This happened insidiously on Friday nights at my grandparents’ house, after everyone else had gone to sleep, including my kid brother, Bill.

Bill was beside me on the floor, dead to the world between two featherbeds. I was wide awake, staring at Papa’s 1955 Motorola black and white television, watching the only show available, the late movie on WKBT. The films I absorbed then, when I was too young to have any sort of artistic taste were, luckily, classics: Random Harvest, Rear Window, High Noon, Frankenstein.

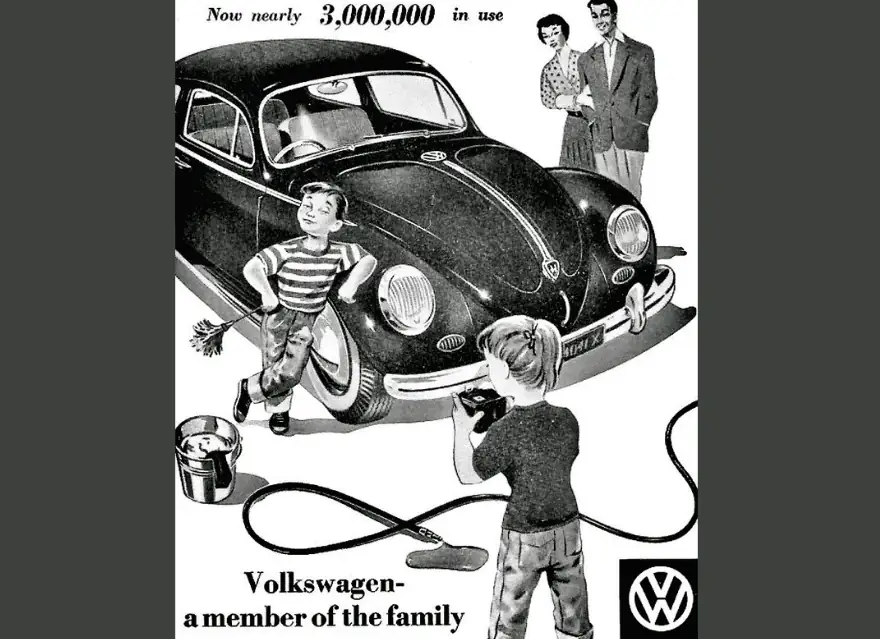

Of course, these life-altering screenings did not come without interruption. The late movie on Channel 8 was sponsored by a lunatic whose name I’ve forgotten. He was selling weird little turtle-shaped foreign cars to the hayseeds of Wisconsin. To break us from our Motown habits, he knew he had to be entertaining —no, crazy. So, he climbed up on top of his latest models, or did screeching, rubber-burning doughnuts in his parking lot. He ranted, cavorted and wore strange costumes. He was fun. He had to be fun. He was selling cars from Mars, otherwise known as Volkswagens.

After getting to know your particular Beetle’s idiosyncrasies, you made a few guesses, tweaked a doo-hickey or two, whispered sweet nothings or sang the car’s favorite song, then slipped into the driver’s seat, turned the key and listened lovingly—eureka!—to the pocketa-pocketa purr of your personal rattletrap.

It wasn’t ’til about a year later that I saw one of these aberrant vehicles on the street. I gazed in a mixture of fascination and trepidation, wondering if this midget machine was the future of automobiles? Of course, the VW Beetle did little to dictate design decisions made in Detroit. But it provided an alternative that my late-movie lunatic had foreseen — affordable conveyance without bells and whistles that performed the basic, vital, unembellished function of getting four people (or five, in a pinch, perhaps including a medium-size dog) from Point A to Point B.

Because of its economic accessibility, the Beetle became widely popular in America and evolved — ironically, because it was the default vehicle of the Third Reich — into the official car of the counterculture.

As time went by, I ended up owning two Beetles. My last one, named Mel (everyone named their Beetles), was serviced by a mechanic in San Carlos, California named Jeff and then by brother Bill. Both Jeff and Bill were “car guys” who had, early in their automotive education, fallen under the spell of that oddball, four-cylinder, four-stroke 1200cc air-cooled engine, which only generated a puny 36 horsepower. When you lifted the hood, everything was visible and within reach and—with a little fooling around — comprehensible.

VWs turned grad students studying Keirkegaard and Wittgenstein into car guys. If you had a Beetle, you eventually fell into tinkering under that flimsy hood, often with tools no more complicated than a flathead screwdriver. After getting to know your particular Beetle’s idiosyncrasies, you made a few guesses, tweaked a doo-hickey or two, whispered sweet nothings or sang the car’s favorite song, then slipped into the driver’s seat, turned the key and listened lovingly— eureka! — to the pocketa-pocketa purr of your personal rattletrap.

Your typical Beetle would run even if not all of its parts were in working order. My friend Schuster drove his VW for three years without the vestige of a second gear. Jeff once repaired Mel by gluing a shaved-down dime into the hole where the compression-cap had popped off and disappeared.

Even for folks disinclined to lift the hood, the beauty of a Beetle was its transcendent simplicity. You settled into a driver’s seat where nothing you beheld offered an intellectual challenge. It was paradise for the automotive moron. All you had to touch were a steering wheel and a four-speed gearshift. The dashboard was a minimal masterpiece — speedometer, odometer and engine-temp heat gauge, the last of which you never looked at. To the right were five knobs, two for the radio and one that might or might not activate an alleged heater. Nothing blinked, nothing beeped, no warnings ever flashed. You diagnosed issues by feel, by the subtle smells that drifted into the cabin, by the sounds that burped and clanked, popped and squeaked when you turned down the (AM) radio.

Owning a Beetle was a marriage governed by moods, conveyed and deepened by hints and whispers. If you had one, it was the most human car you ever drove. Each Bug had a personality. You got to know it, you compensated for its quirks and, somehow, the damn thing got to know you so personally that other people had trouble driving it. Until that fateful day when it threw a rod or died in an eerily human heap, enveloped in steam and leaking rainbow fluids, on the shoulder of Route 20 or I-90, it would stand by you as loyally as Ben E. King.

The Volkswagen folks made a strange mistake this month, airing a Super Bowl ad (see the YouTube video below) that reminded people of that bygone era of simple Beetles and lunatic late-show car dealers. The contrast between those anthropomorphic Bugs of yore and today’s sleek, trend-conscious VWs, indistinguishable from a Benz or a Buick, did not favor the new wave. Grainy black-and-white clips of those old cars stirred memories and summoned nostalgia. The new ones left an emotional void.

Worse, the new ones boast and promote — without a second thought — a dizzying panoply of distractions, diversions and invitations to driver complacency. The thoroughly modern front seat has become a province of screens, projections, voices and sounding gongs. Your late-model, ADAS-equipped, AV-incipient VW, Ford or Tesla cossets the illusion of autonomy, the seductive suggestion that the machine knows better than you what it’s doing, that its interactive “center stack,” its flashing lights, nagging noises and mysterious symbols, glowing yellow on a dashboard as crowded as the cockpit of a 787, will warn you before it’s too late and guide you unscathed through the Mad Max carnage of Maple Street.

As I follow the escalation of automotive technology — and its price — I recall my crazy late-show sponsor as the happiest car dealer I’ve ever seen. And I know why. He wasn’t selling options, extras and driver assistance. He wasn’t pitching power, speed, luxury and sex. He wasn’t even touting the allure of trendy design. Every Beetle looked the same. He was the purveyor of simplicity and he knew, intuitively, that millions of people cherished the idea of a car whose sole purpose was to do what a horse used to do. Get you there.

Lately, I harbor the hope that some crafty carmaker will seize the notion of a “simple car,” possibly electric because electricity is much simpler than internal combustion. It would offer its driver nothing to behold besides the wheel, a few gauges for speed, mileage, temperature and headlights. The heater should work and the radio should get FM stations. The seats would be comfy but not so much that you’d want to live there. This simple car would be distinctive by what it lacks. Autonomy would be out of the question. Infotainment would consist of, at best, conversation, or, at worst, kids in the back seat glued to their mobile phones. Instead of a center stack, an arm rest. There would be no cradle for the driver’s phone. So, instead of GPS, Rand McNally.

Not everyone would want a car so basic. But Volkswagen once proved to the world — and then forgot — that the market for a car barely more complicated than a MixMaster and Puritanically devoid of “luxury,” was huge. As we drive pell-mell into an era of artificial intelligence, bewildering technology and “computers on wheels,” someone must suspect that this market is still there, simmering beneath the surface of consumer frustration. After 75 years of planned obsolescence and feature creep, now might be the ideal — and profitable — moment to heed the advice of Thoreau and “simplify, simplify.”

David Benjamin, an author, essayist and veteran journalist, has been examining the human element in high technology for more than 20 years. His novels and non-fiction books, published by Last Kid Books, have won more than a dozen literary awards. Most recently, his coming-of-age novel, They Shot Kennedy, had won the 2021 Midwest Book award in the category of literary/contemporary/historical fiction.

Copyright permission/reprint service of a full Ojo-Yoshida Report story is available for promotional use on your website, marketing materials and social media promotions. Please send us an email at talktous@ojoyoshidareport.com for details.