By Colin Barnden

What’s at stake?

Autonomous driving is facing an extinction-level event. This industry will die without an immediate, unambiguous, and robust answer to the question: Why robo-drivers?

Ford is shutting down Argo AI. We have reported extensively on its demise and questioned the wisdom of an industry throwing billions of dollars into R&D for autonomous taxis, toasters and trucks.

Others have reported on Ford’s decision to abandon autonomous driving technology.

Cruise and Waymo responded to the Argo news in accordance with their modus operandi: more PR. Cruise said it was expanding its operational design domain to include most of San Francisco. Waymo, meanwhile, announced the launch of autonomous taxi services to Phoenix’s Sky Harbor Airport.

Let’s consider those two developments.

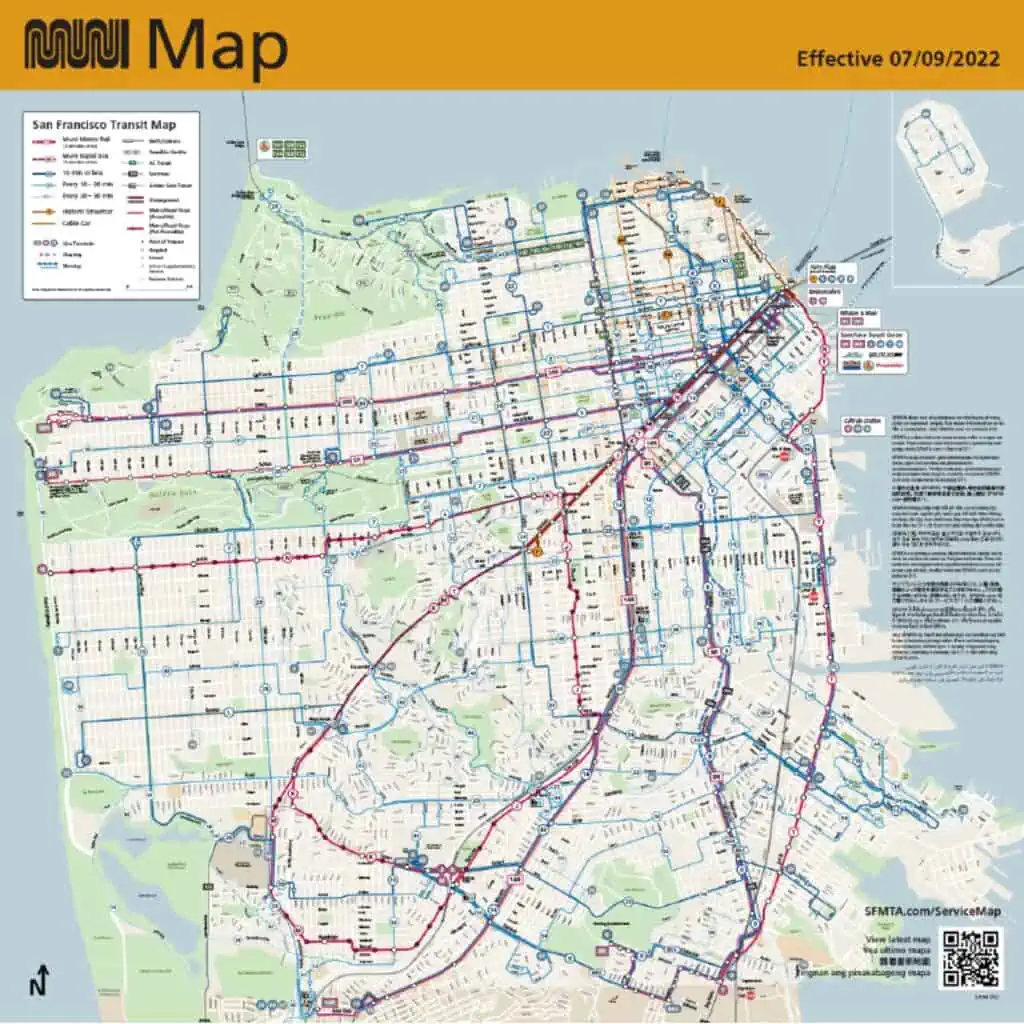

Below is Cruise’s newly expanded coverage area in San Francisco.

Compare that to a map of the San Francisco Municipal Railway, the public transit system that operates buses, trolleybuses, light rail, streetcars, and cable cars.

SF Muni has annual ridership of about 90 million. So, how much benefit is Cruise really bringing to San Francisco’s transit system?

Meanwhile, Waymo boasts it is the first robotaxi operator to launch paid trips to and from an airport. But consider, human-driven taxis have picked up and dropped off customers at airports for decades. What is Waymo adding, besides autonomous driving?

Cruise is also spending billions to compete with a public mass-transit system, while Waymo is spending billions to compete with dudes driving taxis.

If robotaxi development is to survive long enough to lead to safe and commercially viable services at scale, Cruise and Waymo need to articulate the unique benefits of the product. The multi-billion-dollar question is therefore: Why robo-drivers?

As co-investors with Volkswagen in Argo AI, Ford evidently asked this question and reached a definitive answer. From there, CEO Jim Farley made the only logical decision to pull the plug.

BlueCruise, it is

Automated driving was first offered by Tesla with Autopilot in 2015. Most automakers now offer a system for hands-free driving on highways, including GM Super Cruise, Nissan ProPilot and Mercedes-Benz Drive Pilot. Ford’s system is called BlueCruise (Lincoln ActiveGlide).

To date there has been no functional standardization of hands-free driving systems between automakers, although the publication of a detailed protocol for Automated Lane Keeping Systems (ALKS) provides the basis for commonality across the industry.

U.N. Regulation 157 for ALKS specifies a system with automated longitudinal and lateral vehicle control, operation only on divided highways, a maximum speed of 130 kph (about 80 mph), and sophisticated driver monitoring to keep drivers engaged in a supervisory role.

Regulation 157 provides a legal framework, thereby opening the door to global adoption of automated highway driving.

Automated driving is incompatible with safety when operated in proximity to “vulnerable road users” (VRUs). The safest driver is alert, engaged, unimpaired, with hands on the wheel, eyes on the road, and mind on the task of driving. Distraction, drowsiness, and impairment are mitigated through the use of sophisticated driver monitoring, such as the system developed by Australia’s Seeing Machines.

On divided highways, and away from VRUs, hands-off driving schemes such as BlueCruise have been shown to offer some benefits in mitigating driver fatigue. However, these are clearly convenience features, not safety systems, and are categorically not “self-driving.” BlueCruise is highly rated by Consumer Reports.

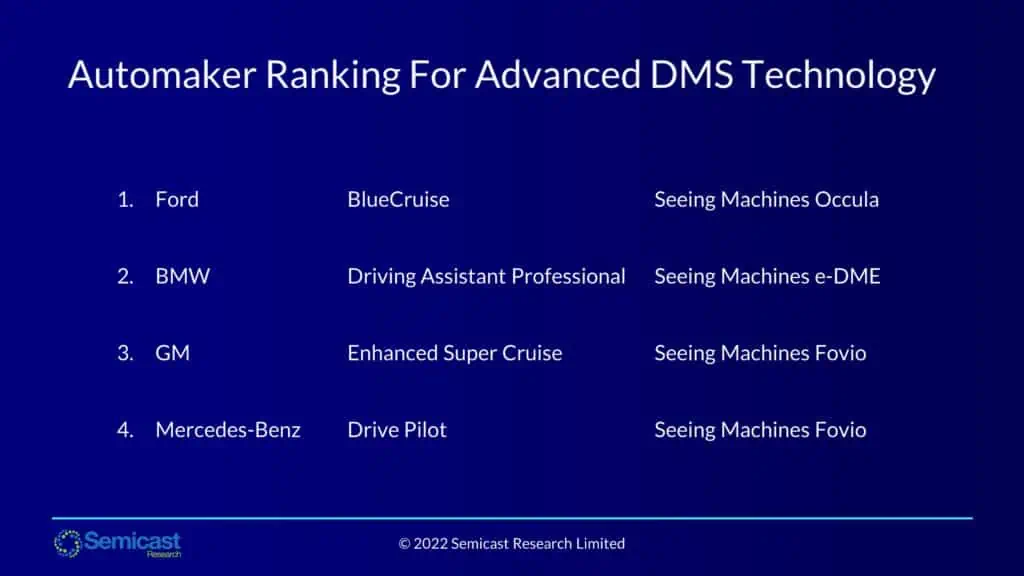

Ford partnered with Mobileye to develop BlueCruise, while research indicates the driver monitoring is supplied by Seeing Machines. BlueCruise is judged to have the most advanced driver monitoring technology in any current production vehicle, ahead of both BMW and GM.

Ford’s customers love BlueCruise and, according to the automaker, 75,000 owners had accumulated more than 16 million hands-free driving miles by the end of August 2022. In September, Ford announced a revised system called BlueCruise 1.2, which added three new features: Lane Change Assist, Predictive Speed Assist, and In-Lane Repositioning.

Ford struck gold with BlueCruise, so the calculations made by Farley about pulling the plug on Argo are easy to deduce. Ford had invested sufficient capital in Argo to commercialize technology which could operate reliably as a proprietary next-generation system for automated highway driving. It already had the foundations for “BlueCruise powered by Argo AI.”

But still unknown was the cost to Ford in continuing to fund Argo to validate and verify an autonomous robo-driver for taxis, or other driverless vehicles such as shuttles and trucks. That development might cost Ford billions more, taking Argo years to complete.

How different the world looked in February 2017, when then then- Ford CEO Mark Fields announced a $1 billion investment in Argo to “develop a virtual driver system for the automaker’s autonomous vehicle coming in 2021.”

We now know Argo’s autonomous development failed the S.M.A.R.T. test (Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Realistic, and Time-bound). That failure required Farley to take decisive action, securing Ford’s future while hanging the noose of AV development around the necks of Cruise and Waymo investors.

BlueCruise it is, robo-drivers are out.

Qualcomm and the Argo-nauts

With a plan to focus development on BlueCruise, and with proprietary automated driving software provided by Argo AI, Ford lacked only an open architecture automotive-grade processor.

Mobileye, Ford’s technology partner in BlueCruise, was the dominant player in automated driving for over a decade, offering its EyeQ family of processors and driving software. But Mobileye’s is a closed architecture, meaning automakers could neither make changes nor run their own software.

As long as there was no viable alternative, most automakers complied. From the EyeQ2 processor through to EyeQ4, Mobileye achieved market dominance. But EyeQ5 fell short, and barely anything has been heard about EyeQ6 since its launch.

The reason? Qualcomm.

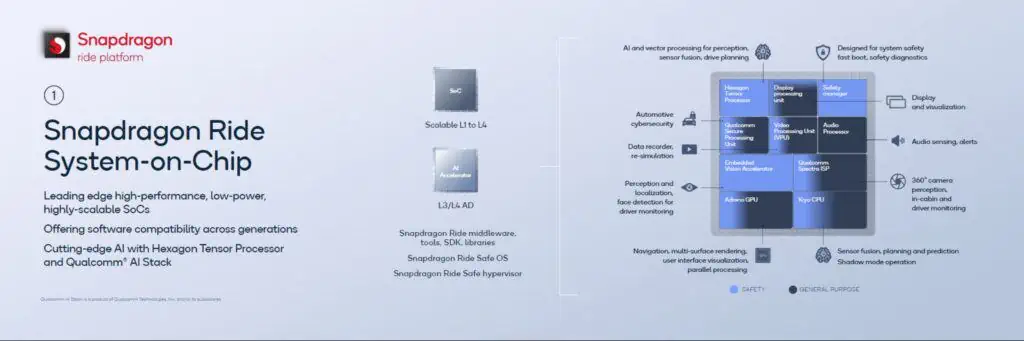

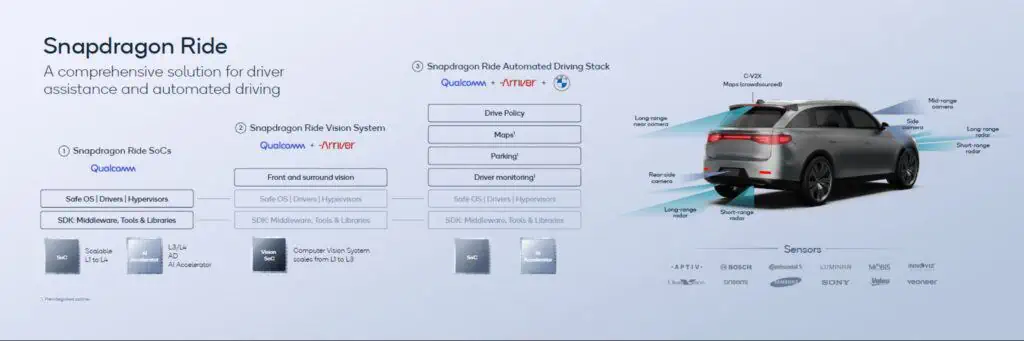

Qualcomm detected the vulnerability in Mobileye’s strategy and calculated that a family of open architecture processors would succeed with the automakers. Thus began the development of the Snapdragon Ride SoC.

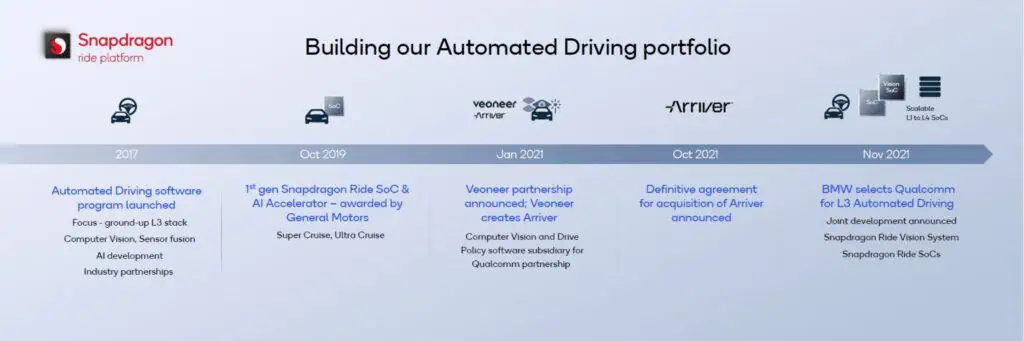

Qualcomm’s first design win was with GM. The first generation of GM’s Super Cruise, as featured in the Cadillac CT6, used Mobileye.

But second-generation Super Cruise and GM Ultra Cruise instead use the Snapdragon Ride SoC, with vision stack and drive policy software developed in-house by the GM Technical Center in Israel. The open architecture enabled GM to write its own software to run on the Qualcomm SoC.

About the same time, Veoneer began working with Qualcomm to take the IP assets acquired from Zenuity and convert its vision stack and drive policy software to run on Qualcomm’s SoCs. The software assets, subsequently named “Arriver,” were acquired by Qualcomm in October 2021.

Thus, the combination of the Snapdragon Ride SoC family with Arriver’s software enabled Qualcomm to directly compete with Mobileye. Compared with Mobileye’s “take it or leave it” approach, Qualcomm was saying, “Take the Arriver software and the chip, or just take the chip and write your own software. It is up to you.”

Automakers are rapidly moving from Mobileye to Qualcomm. GM was the first automaker to take the open architecture route, followed by Volkswagen. Meanwhile BMW is lead technology partner for the “chip and Arriver software” option, having partnered with Mobileye for years.

Why are we witnessing the fracturing of automated driving software into multiple proprietary stacks? It is the natural outcome of Qualcomm’s decision to develop an open architecture, enabling automakers to write their own code.

Qualcomm brilliantly exposed Mobileye’s weakness. In July, Mobileye followed Qualcomm’s lead, opening up its development platform.

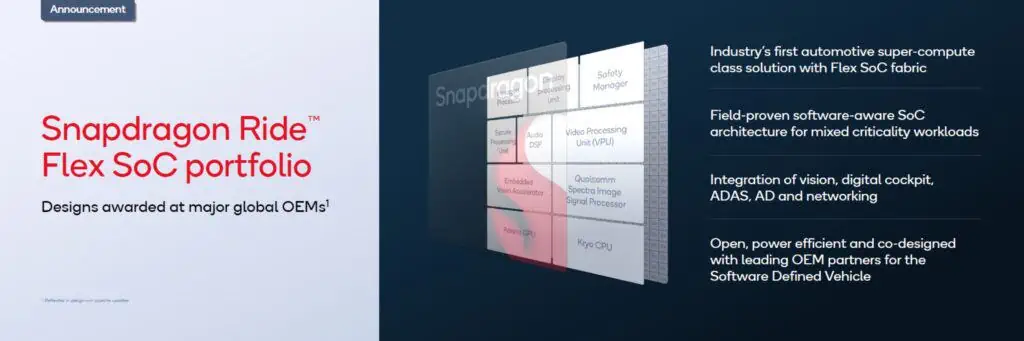

Seen in the wider context of the Qualcomm ecosystem, Ford’s plans for the Argo software and the future of BlueCruise are easy to deduce. Ford is taking Qualcomm’s “chip and own software” route, with the working assumption that it is among the major global automakers already signed up for the Snapdragon Ride Flex SoC.

We’ll know more in January when Qualcomm makes its announcements at the Consumer Electronics Show.

What’s next?

Still lurking is Nvidia, which for years has battled Mobileye over processor specifications and autonomous leadership. There is little doubt Nvidia’s Drive Thor processor provides competition for Qualcomm’s Snapdragon Ride Flex SoC. However, Nvidia lacks an automated driving stack comparable to Arriver.

The AV industry’s current difficulties present Nvidia with options to acquire a publicly-traded, full-stack developer at an attractive price. An obvious candidate is Aurora Innovation, which as of this writing was valued at $2.3 billion. That compares with the $4.5 billion paid for Arriver by Qualcomm (Mobileye’s current valuation of about $20 billion).

For now, attention is shifting away from autonomous driving developers to suppliers of driver monitoring technology. Seeing Machines is the clear technology leader.

Following Ford’s pivot from autonomous development to automated highway driving, momentum has now dramatically switched from technology starlets to established automakers. With rising interest rates, high inflation, and falling equity valuations, automakers have both the scale and financial muscle to survive tough economic times.

GM’s long-term future is not in doubt, and it could quickly scuttle Cruise to focus resources onto Super Cruise and Ultra Cruise.

That leaves Waymo, originally the Google self-driving car project and the poster child of autonomous driving development, with the most uncertain future. Valued in 2018 at a now ludicrous $175 billion, Waymo has no automaker parent to turn to for funding if the global economy tanks.

The future of robo-driver development now looks dependent on continued investment from innovation and vision funds with deep pockets. In other words, those who have drunk the autonomous Kool-Aid and don’t perform S.M.A.R.T. analysis.

In the financial world there may be other labels for such visionary investors. In poker, they are called suckers.

Colin Barnden is principal analyst at Semicast Research. He can be reached at colin.barnden@semicast.net.

Copyright permission/reprint service of a full Ojo-Yoshida Report story is available for promotional use on your website, marketing materials and social media promotions. Please send us an email at talktous@ojoyoshidareport.com for details.